Puzzles in the process

Dr Hine writes:

Sometimes the process of digitising throws up puzzles. Cassirer’s Categories have not been published previously. As documented in this older post, they have, till now, existed only as a springbound typescript, a two-volume photocopy of the same (with additional pagination and manual highlights) and a summary index.

Sin and cross-referencing

The typescript original uses a cross-reference system based on the independent pagination of each Category. Where additions were made in a later phase of work, such pages constitute a separate “add.” sequence, triggering a restart of the numbering. Thus the thirtieth category, Sin, has five pages in the initial sequence and five more in the addenda. Each bears the running head “(Sin.)”, together with a page number. The internal cross-referencing seems to refer only to the initial sequence, but is present in both. The following is a list of the category’s pages, according to the typescript numbering system:

Sin 1

Sin 2

Sin 3

Sin 4

Sin 5

Sin add. 1

Sin add. 2

Sin add. 3

Sin add. 4

Sin add. 5

An obvious inference from the cross-referencing is that the categories had already been concorded in some fashion before they were typed. In support of this inference, as alluded to in the previous post, among papers deposited at Sheffield are small ringbinders in Cassirer’s own hand, which collate passages from Paul, as well as from Acts, the “Old Testament” prophets, and Kant. Those collations are very strongly linked to Cassirer’s monograph, Grace and Law, in which parallel sequences of quotation appear. This shows us that the arrangement into categories was part of Cassirer’s scholarly approach. (One might espy a need for and semblance of this approach in his dissertation on Aristotle, where Cassirer interprets De Anima in the context of the ancient philosopher’s wider works, applying philological attention to detail.)

Because of the complex relations between the versions, and the significance of the cross-referencing (which is sometimes “for context”, sometimes “also copied in”, and occasionally for some other reason) it was determined that the best solution for digitising and publishing the categories was to provide a diplomatic transcription of the English portion supplemented by images of the original (a facsimile). The “diplomatic” aspect recognises that there is no point duplicating errors, especially where these are obviously typographical.

As the work has progressed, some of the transcription decisions have become harder. As one becomes attentive to the patterns of the typewriting, questions arise that make one think harder about what’s happening. Category 30 offers some apt examples.

An unexplained abandonment in category 30 (Sin)

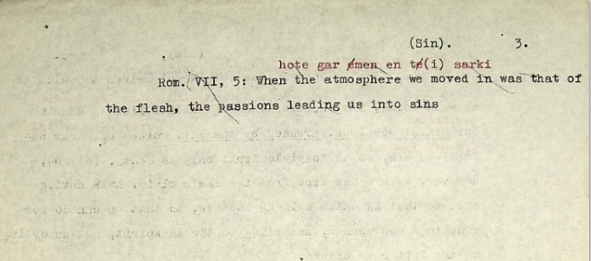

In the first place, we have a tangible ‘artefact’ of the process. In the main sequence, on the verso (rear, reverse) of page 3 is an abortive page 3, with the opening of Romans 7:5. It reads, “When the atmosphere we moved in was that of the flesh, the passions leading us into sins”. Above the line is the Greek phrase “ὅτε γὰρ ἦμεν ἐν τῇ σαρκί”, or as per the typewriter “hote gar émen en té(i) sarki”. This corresponds to the opening English clause. All the text on this side has been struck through by hand.

This detail shows the abandoned opening to page 3, as it appears on the rear of the full version. The rear side, known technically as the verso, is typically blank.

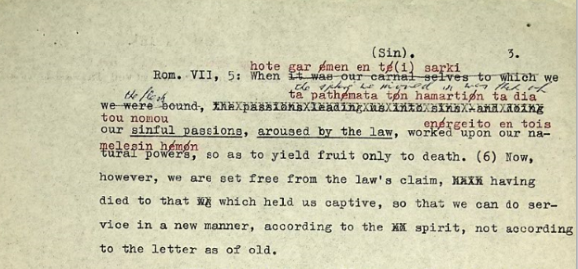

On the opposite side (the recto, or what, if you’ll excuse the complexity, was perhaps the original verso) we find a complete page 3. This also begins with Romans 7:5, but now the typed text opens: “When it was our carnal selves to which we we [sic] were bound”. All but the first “When” is then struck out by hand, and Cassirer has written beneath “the sphere we moved in was that of the flesh”. The next clause had already been corrected on the typewriter, with “the passions leading us into sins - and doing” mechanically struck out.

This detail shows the text of Romans 7:5 as it appears on the completed page 3 in the original sequence. The combination of amendments is clearly visible.

A fine puzzle.

On the one hand, we may be sure that both English and Greek texts were being entered in alternate lines where needed. (And on investigating, it is a perfectly normal facet of a typewriter to hold both red and black ribbons in tandem.)

Such an explanation also helps to account for the presence of “we we” in the main rendering of Romans 7:5, since one is at the end of a line and one begins the next line. If the typist had stopped to switch to interlinear Greek, the accidental duplication could more easily arise. It is a challenge to hold concentration in two languages.

If the present verso was in fact an initial recto, then it might be the use of “atmosphere” (where we find later “sphere”) had offended. But then one could simply strike through “atmo”. A simple fix, and less damaging than that overleaf, this would have been a characteristic amendment. Furthermore, the similar wording (“sphere” for atmosphere) appears only in the handwritten editing, which logically belongs to a separate round—since Cassirer was not his own typist.

The addenda provide no further illumination, since there the opening phrase reads “While it was flesh that ((ruled)) our lives”. Within God’s New Covenant, the same phrase is given as “And indeed at the time when it was our lower nature which determined what we did”. (If nothing else, this parade of texts serves to show the ongoing nature of Cassirer’s translation effort.)

Sin's true colours

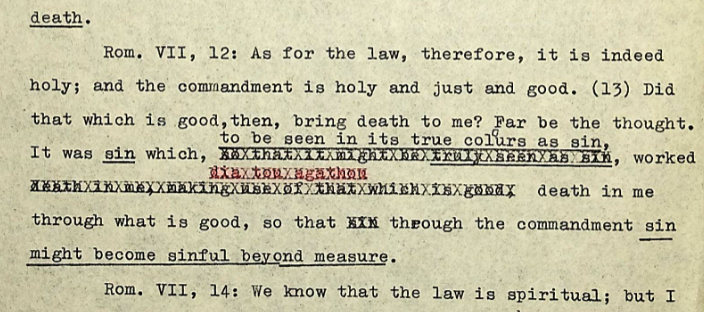

This page of Sin provides another intriguing incident, this time in the transcription of Romans 7:13. Here the amendment is typewritten. The text begins:

“It was sin which, so that it might be truly seen as sin, worked death in me, making use of that which is good”

Between the lines is the Greek phrase διὰ τοῦ ἀγαθου (dia tou agathou), corresponding roughly to the English “that which is good”.

The text then cuts off abruptly, the strings “so … sin” and “death … good” being struck out, along with the Greek words. A further text is typed above, a more paraphrastic rendering: “to be seen in its true colours as sin [worked]”, and the translation resumes where it had left off, repeating the earlier “death in me” and adding the more direct “through what is good”. Three words further along, “sin” has been struck out, to allow for a reordering of expression. Again, this change seems to have arisen in the midst of the act of typing, since “sin” now appears at the end of the same typed line.

The obvious question is, if Cassirer himself was not the typist, on what basis do changes happen in the midst of the act of typing? These are not changes of the kind an amanuensis produces. So was Cassirer present? Narrating?

If one were to diplomatically transcribe only a corrected version of the final text, we would miss the interplay and the implied transactions. So, if you observe increased attention to changes in the textual artefact as the transcriptions progress, it is precisely because we have realised that some of these details are worth capturing and meditating upon.

Note also that at the end of verse 13, a portion of the underlining is noticeably off kilter. Perhaps it had been forgotten?